Understanding the difference between letter names and letter sounds is one of the first steps of phonics instruction. People often use letter and sound interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing. Let’s explore why letters and sounds are different . We will also explore strategies to teach these concepts to our students in a simple and meaningful way.

Would you rather listen or watch? Find a podcast version of this blog post here, or watch the video below.

What is a letter name?

When people refer to letters, they typically are thinking about letter names. For example, if I write ABC, you will read that by saying the name of the letter (like when you sing the alphabet song). These are the letter names. Each of the 26 letters in the English alphabet has a single name. For example, the word bat begins with the letter b. B is the name of this letter- b. We use letter names when we’re referring to specific letters, just like we use our friend’s names when we’re talking about them.

What is a letter sound?

When we refer to a letter sound, we are referring to the sound we make when we’re reading and we see a specific letter. For example, if I write the word cat, you didn’t say the names of those letter- C A T, you said the word- cat. If we break it down, you said these sounds quickly- /c/ /a/ /t/. Fluent readers blend, or slide, sounds together quickly to read words.

While there are 26 letters in the alphabet, there are 44 sounds, or phonemes, in the English language. If you’re good at math, you might have noticed that there are more sounds than letters in the English language. Unlike other languages, English doesn’t have a one to one correspondence between letters and sounds. In other words, letters can (and often do) represent more than one sound depending on the word. And, some sounds require more than one letter to be spelled out.

The main difference is that letters are written and sounds are spoken, and using each term correctly and consistently will help your students with their reading and writing journey. There are some vocabulary that students don’t really need to know to be successful readers and writers- for example grapheme and phoneme. However, it’s important for them to understand what you mean when you ask for a letter vs a sound. More on that below.

Do letters “make” sounds?

Before we go further, I need to address some wording. Often times, people say that a letter “makes” a sound. This is inaccurate. While it might seem nitpicky, stick with me here. As I mentioned in my first post in the Phonics Rules for Teachers series, reading and writing are not natural processes. Spoken language came before reading and writing. When humans began writing, they had to develop symbols (i.e. letters) to represent the sounds in words. As I mentioned before, English has 26 letters, but 44 sounds. Each letter doesn’t “make” only a single sound.

Children are very literal, so if we tell them a letter “makes” a sound, they’re likely to think it will always “make” that sound. Instead, we can teach them that spoken language came before writing. People did their best to show the sounds we made in our words with letters, and that some letters represent, or stand for, multiple sounds depending on how they’re used.

Let’s look at an example. What sound does this letter represent- a? Did you make the sound you hear in cat? Or maybe the sound you hear in apron? You probably said one of those. But what about the sound a represents in water or was? So, before we talk about letter sounds, remember that they represent many sounds.

How do we spell sounds?

We use letters to spell sounds. While many of the 44 sounds in English are spelled with just 1 letter, there are many sounds that are spelled with 2 or more letters. The letter or letters used to spell sounds are called graphemes. For example, we can spell the long a sound (example apron)- these ways- a, a_e, ai, ay, ea, ey, ei, eigh. Don’t believe me? Check out these words- apron, ape, pay, steak, they, rein, eight.

With any sound, there are more and lesson common ways to spell it, so in phonics instruction, we start with the most common spellings and over time learn the less common spellings.

Why do students need to understand the difference between letter names and letter sounds?

Here’s why it’s important for you to explain the difference between letters and sounds to your students. When they’re just beginning to read and write, sure they could say cat is spelled /c/ /a/ /t/. However, as they grow as readers and writers, “spelling” with sounds will no longer work. For example, if you asked a student to tell you how to spell shop, if they say /sh/ /o/ /p/, do they know the two letters that represent the /sh/ sound? Or, maybe they could say /s/ /h/ /o/ /p/, but that’s counter intuitive and will get trickier as the words they are working with get bigger and they have multiple letters that represent a sound.

Should students learn letter names or sounds first?

If you’re teaching preschool students or early kindergarten students, you can work on hearing and breaking apart sounds in words before naming letters. In fact, this is a great warm up, even for older students. You can say words for example- hug- and have students break the sounds apart- /h/ /u/ /g/. You can also do the opposite, where you say the sounds and students blend them together. While doing this, it’s vital that you and your students don’t add an /uh/ sound to the end of sounds. For example, cat isn’t /cuh/ /auh/ /tuh/. Model proper letter pronunciation, and make sure students are doing the same. For students who struggle with this, I tell them to make a scissor motion with their hand and to clip the sound. We also joke that U is the only letter that has an /uh/.

When you begin teaching letters and sounds, there are a few different schools of thought on which students should learn first: letter names vs letter sounds. While there’s not a clear answer, it is important that students learn both. In my experience, most students benefit from learning both at the same time. Of course, some letters represent more than one sound, but we start with the most common. In a future post, I will discuss further the order to teach sounds. If you’re already spending time discussing the sound that a letter represents, it’s not going to take much more brain power for a student to learn the name as well.

How can we help understand the difference between letter names and sounds?

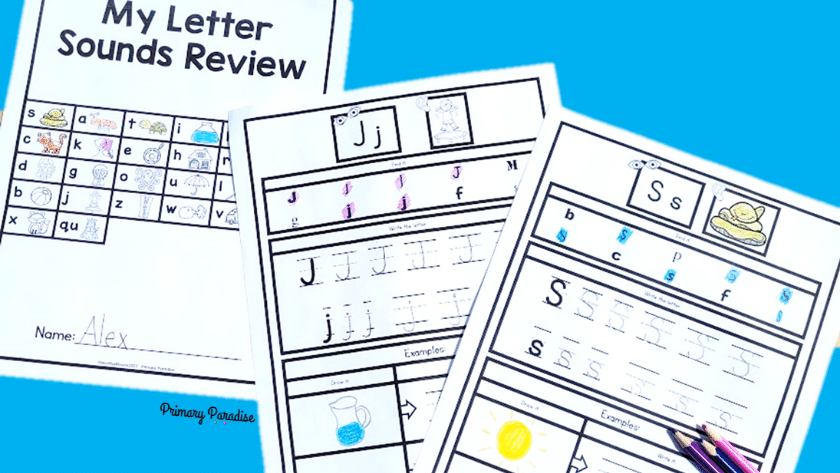

As a first grade teacher, some of my students come to me already knowing letter names and sounds, but most still don’t know both solidly. I begin each school year with a letter name, sound, and formation review (which you can read all about here). Since I teach grade 1, and often my students have some knowledge of letters, sounds, and how to form letters, I focus on all three at once.

However, many of my students already have learned incorrectly, or have incomplete knowledge. The best thing we can do is ensure that students have a good foundation from the beginning. The second best thing is to give them a solid letter sound and name foundation as soon as we can.

6 strategies to teach letter names and sounds

- Teach letter names and sounds together– As I said, if you’re teaching that A represents /a/, calling it an A at the same time just makes sense. Many phonics programs have helpful hand motions, chants, keywords, and rhymes to help with this. These are great as a bridge, but the ultimate goal should be for students to be able to eventually not need these extra support. You don’t need to rush this, but we don’t want 10 year olds still relying on these cues. We want, over time, for this to become automatic.

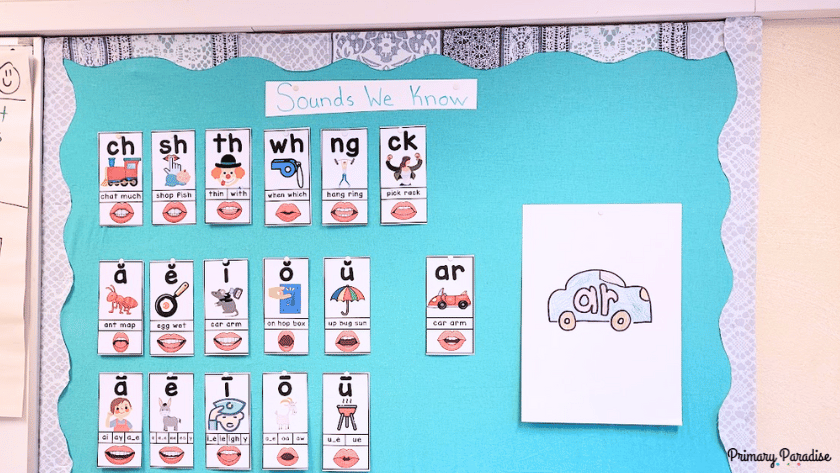

- Focus on what their mouth is doing- When initially teaching letter sounds, focus on the placement of the mouth and tongue. Showing students what their lips, tongue, and mouth are doing will help with proper pronunciation. If possible, give them mirrors so they can look at what the sound looks like. Using a sound wall with picture prompts (particularly pictures of real mouths) is invaluable.

- Use the letters as soon as possible– A great way to help students not rely on hand motions, chants, or keywords for too long is to start using letters in words as soon as possible. Once students know a handful of letters, you can start building 2 and 3 letter words together. This allows them to practice spelling (saying the names), and reading (making the sounds) in context quickly.

- Think about pacing– Hopefully your phonics curriculum has a pacing guide that is developmentally appropriate. However, many teachers don’t have a strong phonics curriculum. If you’re figuring it out yourself, think about pacing. I’ll cover the order to teach sounds in a future post. However, gone are the days of spending a full week on a letter. I find focusing on a few letters each week while continuously reviewing letters that you’ve already learned works the best. Students are able to begin to use them in context. And, if you spend time reviewing each day, it will help solidify any letters they might not have a firm grasp on yet.

- Use clear language– From the beginning, talk about letters having names and sounds they can represent. Tell your students that every letter has only one name, but can represent one or more sounds. I like to use a kid as an illustration. Pull a student to the front and ask them to say their name. This is Alex. Alex is their name. Alex can do many things. What can Alex do? Students might say things like- sit, stand, jump, run. Connect this to letters. This is an A. It’s name is A. A can do many things in words. It can represent different sounds- in cat, A represents /a/. As we learn more about A, we’ll learn more sounds A can represent.

- Use warm ups to tune into sounds– As I mentioned above, you can help get students used to breaking apart (segmenting) and building (blending) words and sounds orally. This is a great warm up before your phonics lesson. It also helps students tune into sounds, and as you learn more letters, you can then add spelling the words as well.

Consistency is key

Here are (hopefully) your biggest takeaways.

- Use consistent language when referring to letter names and sounds.

- Teach your students letter names and sounds together for each letter.

- Segment and blend orally as a warm up, making sure to model and reinforce correct letter sound pronunciation.

- Teach a few sounds each week. You don’t need to spend too long on a single letter in isolation.

- Review all sounds students have learned so far consistently.

- Use new letters and sounds in context early, often, and consistently.

Understanding the difference between letter names and letter sounds is fundamental in phonics education. Helping our students learn the difference and use them properly is one of the first steps to building a solid reading foundation.